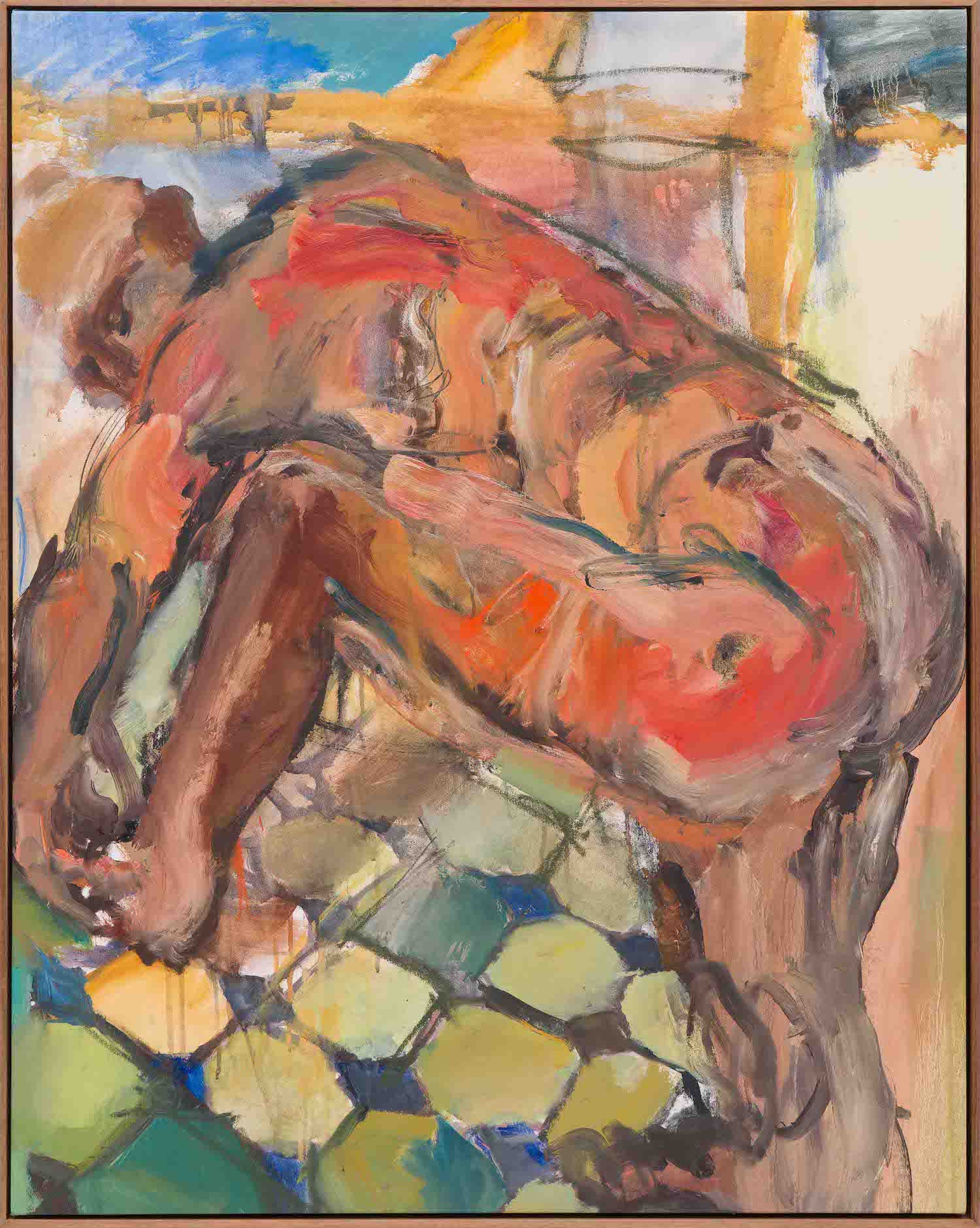

Denis Clarke | Reconfiguration

Denis Clarke | Reconfiguration

Taking risks and playing with medium; the fluid of paint, ink or the brittle softness of charcoal, represented artist Denis Clarke is a painter interested in ‘creating a process of informed experiment’. In this interview, Clarke reflects on his early years and the significance of theatre, neo-expressionism and time spent in London to his practice.

Claire de Carteret: Hi Denis, thank you so much for taking the time to chat with me. You’ve been painting for many years now, when and why did you start?

Denis Clarke: I remember doing a painting when I was about 8 years old and my mother's excitement at seeing it at the school open day. Then later, the joy of feeling that paint is a substance that can be manipulated in response to a subject, that there was no rule as to having to copy it. In school the art room was my favourite place. I felt connected, I was in the right place, I kind of owned that space. It was me.

de Carteret: Can you talk about how your move to London and studying at St Martins School of Art influenced your perspective?

Clarke: The work I liked the most at St Martins was coming from the sculpture department. I would make trips to the basement to check out what was happening. I was young, innocent and away from suburban subject matter that I was so familiar with. It seemed that both sculpture and painting, apart from a few exceptions, had to be purely abstract and large. What happened to the figure or the landscape in painting?

It was a difficult time, working to one’s next stage. I started constructing multi panel paintings but in the end, I deconstructed the stretched canvases to single units which I painted a series of semi abstract landscapes with oil, abandoning acrylic as being too plastic. It was a return to something more sensuous and I was using London as my reference for the first time.

de Carteret: Can you talk about the relationship between drawing and painting in your practice? Are they intertwined and how do they inform each other?

Clarke: They are intertwined. It’s as if I find my bearings through drawing. It’s about finding a connection and realisation to the potential that lies within a subject and being able to see shapes and colours that might be released through the act of looking. Drawing is a bit like taking a medical assessment of yourself. Looking to see what one can see, and what might be possible at a particular time according to your mental processes or state. Drawing of course can define space and underpin structure even though it may well disappear in the act of painting, despite its lingering evidence.

de Carteret: What has been the significance of theatre, dramatauge and opera to your practice?

Clarke: I was very fortunate to be invited to partake in the realization of two opera productions in 1981-82, in Zurich and London. On stage an actor needs to be acutely psychologically attuned to the role they are playing. At an advanced level this requires risk and flexibility. I was particularly interested in the process of improvisation, which was employed in the early stage of rehearsal. Characters were developed through trial and error ‘drawing’ on their own observations, not dissimilar to preparing for a painting.

de Carteret: How does performance inform subject matter or process for you?

Clarke: Seeing these performances inspired me to see the figure as being central to psychological aspects of human nature. It was really from this point of view that my work had a relationship by chance to neo-expressionism. My interests revolved around movement, gesture and strong colour. I felt I had unintentionally wandered into the expressionist camp with my Picadilly Circus series 1980, which was based on a dramatic altercation I witnessed in Piccadilly.

de Carteret: How do you feel about being contextualised within the neo-expressionism movement now?

Clarke: Neo Expressionism was a breath of fresh air. The thing is as a young painter you are searching for some kind of validation or like-minded company. With more minimal and conceptual art forms growing in popularity there was the feeling it was irrelevant and out of touch to be painting figuratively and using paint to express ideas and passionate emotions.

de Carteret: Was there a shift in your practice when you returned to Australia in 1998? Can you describe what happened?

Clarke: My work for the first years back in Australia dealt with re-discovering the feel and atmosphere of Sydney. For example, electricity poles and their intricate linear patterns of wires. Corrugated roofing also exerted a magnetic pull over me. I was responding to the superficial graphic rather than digesting the outward appearance. Resolving an image or composition that had a depth and allure achieved through a more thoughtful process. Perhaps the more expansive paintings I did at this time were the Civilisation Series which were developed through many trips to draw at St Peter’s in Sydney.

de Carteret: Throughout your career, to what extent has locality and place been significant to your visual language?

Clarke: There has always been two aspects to my explorations. Nature has always exerted a fascination for me. It presents a never-ending parade of phenomena which intricately collide and form tempting creative souls to make metaphors about its enormous scale and impact.

Working from the urban environment initially involves a more restricted subject and in way, a tougher intellectual application. It is perhaps more revealing of myself. Drier, constructed imagery and the workings of form and space. I have always found it strangely pleasing to draw outside at a site that is for all purposes ‘un-scenic’. I have found Petersham and Marrickville very conducive to my work. I am not wishing to make a scenic rendition of a site, rather I am wanting to open my gaze to the impact of space and movement of figures in order to carry this experience back to my studio.

de Carteret: When you’re working in nature, how do you choose subject matter?

Clarke: Working in nature affords the possibility of carrying out a meditation on the subject so that one feels at liberty to experiment and respond to sensations received. I am interested in en plein air from the angle that one attempts to re-see a new interpretation.

The painting ‘Newee Creek’ was entirely painted outside, whereas ‘Sofala 2’ is worked from reference materials such as drawings which help in the realisation of the painting.

de Carteret: What are the differences of working from built environments than from natural ones?

Clarke: In built environments you are working with verticality, horizontality and sharp edges and structure which define urban spaces. However, there are organic elements to the feel of buildings just in the way light plays on them. Architectural elements such as arches relate to trees.

Generally greater energy is required to research the built environment. Working outside involves a faster pace with noise and movement compared to Natural but it can be more edgy and it's more about people.

"I am interested in en plein air from the angle that one attempts to re-see a new interpretation"

de Carteret: What would you say to an art student on their first day of art school today?

Clarke: Channel your uncertainties into your art or an aspect of your practice you feel drawn to. Make them work for you.

de Carteret: If you weren’t an artist what would you be?

Clarke: A Musician!