Time erodes. It slides across a scene like a second shutter, obliterating narrative.

Everyone has old family photos and as a kid you grow up with the stories that go with them. My dad took lots of photos and whenever we went through them he could provide a pretty good running commentary about who was who and how their lives had played out. But now, there’s often a gap in the narration, I don’t remember the details as he did. I wish I’d written down who everyone was and dad’s gone now. So faces look out , absorbed in that moment in their life but they are people in a photo who've lost their story. Their context is gone. All that remains is dad’s cryptic fragments of description. Hints of a story. How fragile we seem. Time pushes us aside.

These paintings are about time, that corrosive shutter.

Exhibition Essay - Susannah Smith

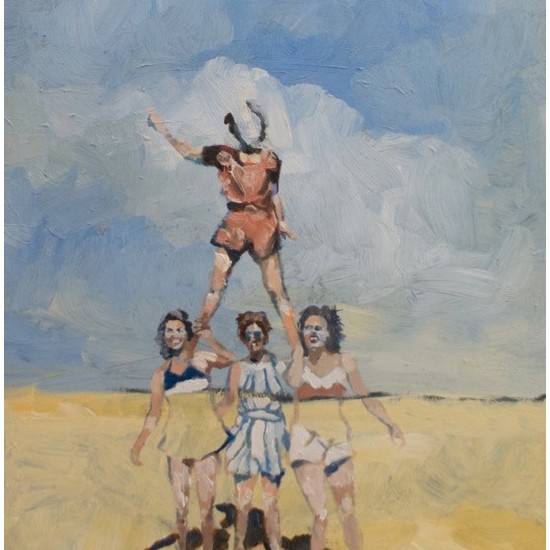

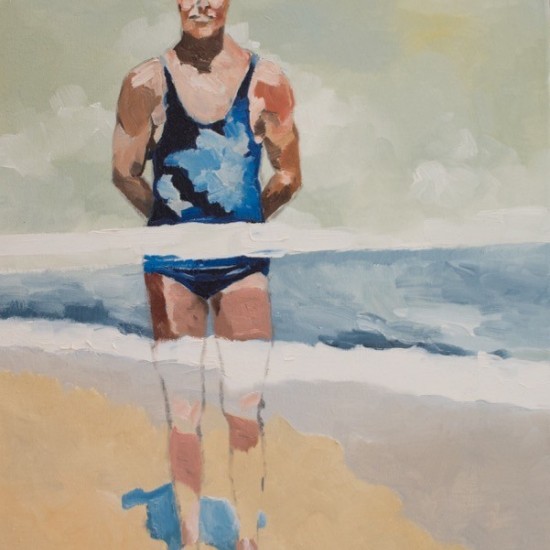

Gestures voice stories of interactions and faces beam with the optimistic exuberance of youth. Others meld away, erased by time as enigmatic snapshots of the past. Behind, waves crash and clouds gather as the beach continues on, stretching back and reaching forward in time, witness to these figures and with a time scale of its own.

Harley Oliver’s latest series ‘Dad Took A Picture’ considers what has gone and what remains with the passing of time. Gaps in memory mirror the gap in time between us and the figures, leaving holes in the images where faces are unrecognised and relationships are unknown.

Harley’s interest in marking this disjuncture plays out in the landscapes of these works. As the figures dissolve he offers us visions of the eternal beaches of Australia’s ancient landmass which were here long before we could make footprints in the sand and which will continue on long after we are gone.

Harley has captured the flatness of Australian coastal light through painterly drama. The figures are embedded into these beaches, frozen in that fraction of a second as the camera shutter closes. He conjures them into frame as if spotlighting the past physically, if only for an elusive moment.

Looking through his father’s photos, Harley was struck by the people he couldn’t place and the personal narratives tantalisingly present in the images, yet now out of reach and lost. Taken on limited rolls of film, each shot was taken for a reason. Harley’s paintings work towards constructing possible narratives, often layering figures from multiple photos in interactions on the eternal plane of the beach. His long and successful career as a television producer, crafting stories, has undoubtedly influenced this process.

Our minds fill in potential stories and complete the missing elements of the pictures in tandem with Harley’s open-ended titles, to recognise a family argument between discordant figures in And Then The Day Got Worse and imagine lives beyond the beach for the woman in Everyone Smoked. Elsewhere, the disjunctive, time-lapse raises further questions in I Think He Died as a clothed man, like that seated in the foreground deckchair, walks into the sea.

As the contexts of the figures shift and they dissolve, Harley questions identity via memory and he brings the fleetingness of life to the fore. Yet at the core of these paintings, the act of capturing and illuminating the figure at a split-second in time bypasses fears of death to celebrate moments of life.

Harley Oliver

Hitters, Grapplers and Strongmen

February 28-March 23, 2018