"My works explore exaggerated and self conceptualised self portraiture in a way that considers arranging the self, objects and landscapes in a way that is carnivalesque and grotesque. The idea of the carnival liberates us from the constraints of everyday life, allowing for a fluid exchange of identities and roles. This idea resonates deeply with the diasporic experience, where identity is often fragmented and multifaceted. I also consider site-specificity, and how the displacement of cultural objects impacts identity formation within diasporic communities. I believe that arts relationship to place can reshape perceptions of identity, and thus paintings not only exist as static objects but engage with the context of their display.

A large consideration in the making of my work is ‘thing-power’, a concept that explores agency within objects, and how non-human entities can possess agency in determining meaning. In these works the self is a clock, the eyes are pool balls, the dresser mirror is a portal to a playground, the pool table is a groomed garden with patterns of i-ching coins. I am interested in the way that patterns travel across time and space and have spiritual meaning or idiosyncratic ones… or both. Scattered in my work are patterns from Han Dynasty tombstones, traditional fortune telling mechanisms and prints on fabric and clothing."

Jacquie Meng graduated from ANU with a Bachelor of Visual Arts (First Class Honours)/ Bachelor of Art History and Curatorship in 2022. She was awarded the Brett Whitely travelling scholarship in 2021, selected as a finalist in 2022 'the churchie' emerging art prize at the IMA, and PICA’s 'Hatched'. In 2023, she took part in residencies include Kunstraum in New York and Pilotenkueche International Art Program in Leipzig and in 2024 she was selected as the recipient of the Waverley Artist Studio residency in Bondi.

In 2023 and 2024 she represented Stanley Street Gallery at the 'Sydney Contemporary' and was also selected for the 2024 Canbera Art Biennial. Meng also exhibited in ‘YEAR OF THE DRAGON’ at 4A Center for Contemporary Asian Art, ‘The Floor is Lava’ with Tiles Gallery and ‘Choose Your Fighter’ with Marvin Gardens New York.

Jacquie was awarded the 2024 Mosman Art Prize - Guy Warren Emerging Artist Award and was a finalist in the Lenn Fox painting prize.

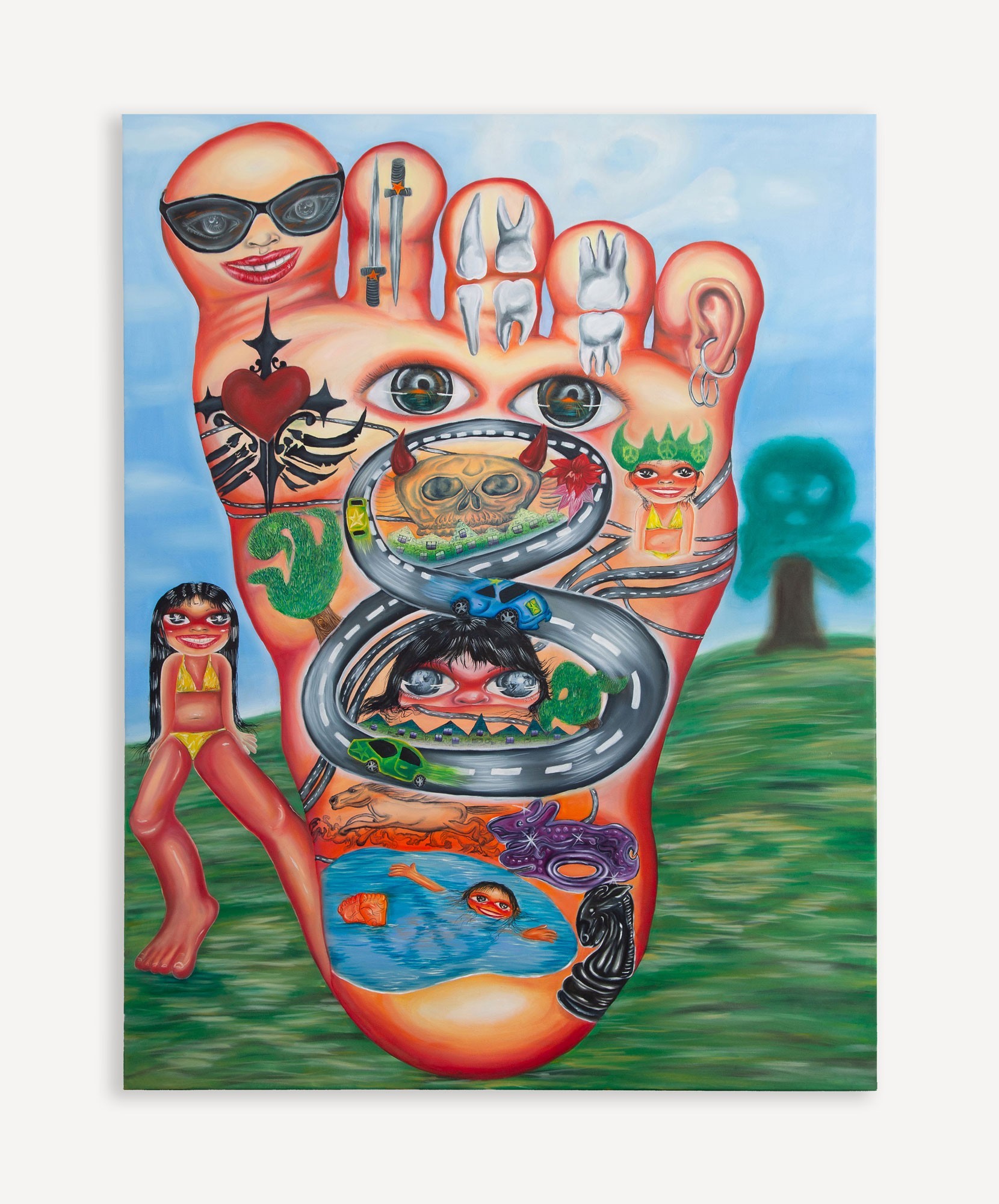

Jacquie Meng, Foot Reflexology, 2024, Oil on canvas, 133 x 102 cm, Image Remy Faint

Jacquie Meng, Foot Reflexology, 2024, Oil on canvas, 133 x 102 cm, Image Remy Faint

Opening Celebration Saturday, 23 November 3-5pm

Artist Talk Friday, December 13 from 6:30pm (Cancelled due to unforseen circumstances)

The World is My Playground

In his book Rabelais and His World, theorist Mikhail Bakhtin uses the literature of François Rabelais to outline the carnivalesque as integral to his theory of art. His history of folklore in literature posits the carnival as the people’s second life: “organized on the basis of laughter. It is a festive life.” The carnival is a rampantly physical, dynamic, antihierarchical event which transforms the participant’s relationship to time and space through sociality, vulgarity and visceral materiality. The carnival allows for the integration of everything that is typically separated by hierarchy. The concurrence of high and low is conducted through the body in carnivalesque roleplay. The jester’s vulgar roleplay is allowed and revered as entertainment; and the jester can play everywhere – even in the palace before the king. At the carnival, everyone is free to transgress. Bakhtin writes: “The material bodily principle is contained … in the people, a people who are continually growing and renewed. This is why all that is bodily becomes grandiose, exaggerated, immeasurable.” In Jacquie Meng’s The World Is My Playground uncanny distortion and self-portraiture as self-roleplay facilitate the emergence of new identities, chance encounters and transformation.

Vulgarity at the carnival is about the body, warping. In The World Is My Playground the foot is a map, the eye is a pool ball, the faces are contorting, and the world is synthetic. Exaggerated self-portraiture goes beyond self-representation into immersion with the thing-power of objects, which have a radiating agency of their own. The textures constituting the spatiality of these works impart the surreal nature of the infraordinary. Smoke, light beams and patterned grass coalesce around the body and objects and are entirely enmeshed. The textural experience of Meng’s works reinforce painting as a practice of playing with space and collapsing time. The self bounds between the paintings: caught in the mirror, braiding hair in bed, soaking in the pool.

Bakhtin described the Carnival as “the true feast of time, the feast of becoming, change, and renewal. It was hostile to all that was immortalized and completed”. In The World Is My Playground the numbers have fallen and a face peers out behind the hands of the clock. Or the clock is on the face itself, in the eye looking outward. Time does not need to be told but goes into flux. The world is not complete. Self, object and spatial entanglement challenge the dread of fixity and immortalisation, making room for the potential something else.

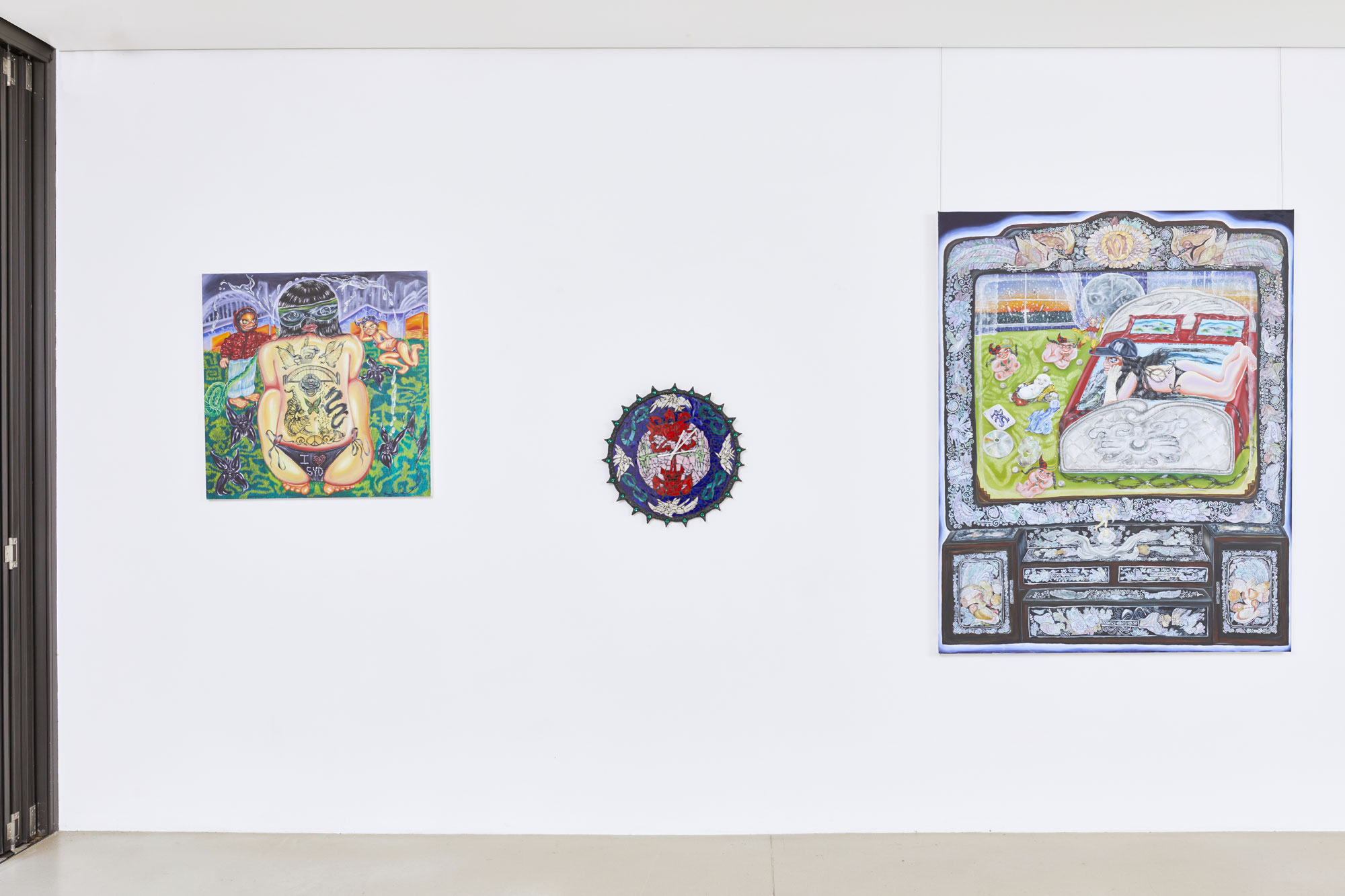

Object-orientation is especially materialised in Meng’s installation practice – the mosaic bench is a monument to sociality, play and the body’s pre-eminence. Mosaic as a form centralises the crack and the irregular. Idiosyncrasy and chance are central to Meng’s world which is made whole through the entanglement of apparently disparate identities (such as East and West) and rejection of aesthetic hierarchies. The imagery selected superimposes the past, present and future through the combined aesthetics of the contemporary, analogue, historic and popular. The World Is My Playground rejects the demarcation of time into a rowdy, encompassing present.

Bakhtin describes the monologue as authoritarian language, and dialogue as communal. The World Is My Playground is a dialogue within itself, the works speak in a shared language of motif and aesthetic but come to the viewer for the final word. And the jester is here too, recognisable through distinct attire and objects, like the marotte. Identity is recognised through symbolism as a transhistorical form of visual communication. The jester reinforces the distinct and known language of the visual world.

In an interview surrealist painter Leonora Carrington rejected the interviewer in their attempts to understand her work in the language of art criticism and history. She responded:

“You’re trying to intellectualise something desperately, and you’re wasting your time… That’s not a way of understanding. To make it kind of into a sort of minilogic. You’ll never understand by that road… Canvas is an empty space… it’s a visual world. You want to turn things into a kind of intellectual game, it’s not.”

Bakhtin was obsessed with language. The World Is My Playground exists as a fundamentally visual world. It’s best not to get lost in the minilogics of art writing, and feel the carnival in the embodied, vulgar, festive visual world of Jacquie Meng.

- Claire Grant

Installation images by Alfonso Chavez-Lujan

Jacquie Meng, Oscar Nimmo & Sibylla Robertson

everything in its right place

July 3-19, 2025