“For makers have to work in a world that does not stand still until the job is completed, and with materials that have properties of their own and are not necessarily predisposed to fall into the shapes required of them, let alone stay in them indefinitely” - Tim Ingold

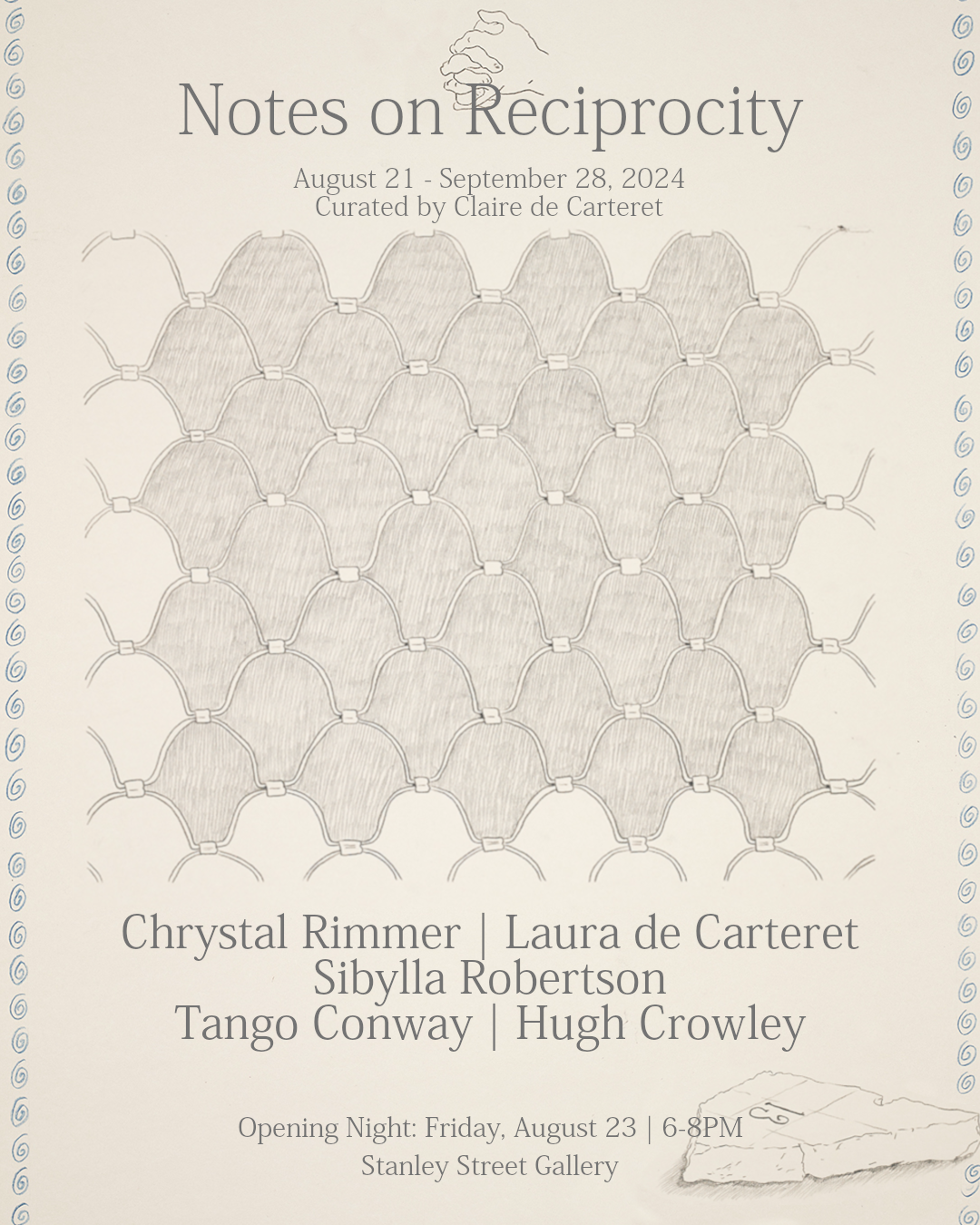

Stanley Street Gallery is delighted to present Notes on Reciprocity a group show curated by Claire de Carteret. Drawing from the text ‘on weaving a basket’ by anthropologist Tim Ingold and lyrics from Lauryn Hill’s album, ‘The Miseducation of Lauryn Hill’, the exhibition is interested in the relationship that grows from spending quality time with material, exploring mutuality in processes of art making where, “mind is not above, nor nature below; if we ask where mind is, it is in the weave of the surface itself” and in this sense brings attention to how ideas don’t always happen in our heads, they are not strictly cognitive; intuition and serendipity are precious forces and we are situated in an ecology of material and the possibility of reciprocity in this is beautiful.

nail polish footpaths

by lily golightly

dedicated to my friends <3

**

daydream melts

and builds a mountain wondering

superspiral electrical, come find me I’m ready

for the wish to come true

like licorice and television

and chaos enduring

life beginning again and again as if it were a dream it is

888 find the portal it’s inside of songs and telephone calls to everyone a perfect day

of sun showers, soap bubbles in mountains,

the cakes in piles of cream and shiny fruits

painted in lip gloss

between sunrises and junk mail

trying to separate realities

you go here and I’ll go there,

spiderweb linking across the cities

the music like magic air

all of the impossibleness

and all of the roses wondering

where does electricity come from inside of the body?

this world full of hell and ribbons

With lace unwinding the universe

I fantasize all day long

Ufo sighting, radio wave,

wattle blooming and convenience stores

we are busy building castles

out of hoop earrings and wings

sandwiches cut into squares

on a train ride into the forest,

leave the world inside of the city behind you

create a new one out of questions

electrical pink !

the day with your name on it

setting fire to memory to at least do something with it

writing letters to Jemi who lives far away and in the middle of the winter a thought erupts

couldn't sleep for hours when I realised

a discovery of anything , I wonder what's going to happen

circles of everything like piles of oranges ready to roll away,

chandeliers, dandelions, notebooks of sentences and bowls of spaghetti in tangles

unravel each one by one as my friend sits beside me saying

he can't remember who he is anymore

cherry stems, freckled leaves and cheeks,

hair clips in curls and chalk board questions,

lie down in the grass now

we can make a plan later,

because of pearls and praying mantis and wondering

let the chaos calm you like pale violet fire

which swims around the morning

before it slowly

slowly

gathers itself

Notes on Reciprocity: Relating to the material

As clichéd as it may be to reference the law of matter, everything is made of something. In other words, the artist can only make what is available to them with the material at hand. But to say more, whatever the artist makes is ultimately a response to the material, and to the world that produced them both.

In his seminal essay, ‘Notes on weaving a basket’ anthropologist Tim Ingold describes what is at work in the act of art making:

First, the practitioner operates within a field of forces set up through his or her engagement with the material; secondly, the work does not merely involve the mechanical application of external force but calls for care, judgement and dexterity; and thirdly, the action has a narrative quality, in the sense that every movement, like every line in a story, grows rhythmically out of the one before and lays the groundwork for the next.

Here, and in characterising craft practices as practices of ‘weaving,’ Ingold intends to contradict both the common understanding of ‘art’—in which the artist is a person of extraordinary creative genius who exacts this upon a given medium—and the common understanding of ‘making’—in which the maker exerts force until the medium complies.

Notes on reciprocity draws on Ingold’s premise that the artist or maker is in relationship with their medium and highlights the way in which the material world gives back to them. As much as the artist/maker/weaver must exercise care and judgement in responding to the conditions set by the material, they are also in a process of revelation. That is, the material reveals possibilities that they are then able to work into; to materialise.

In Chrystal Rimmer’s work, the dichotomy between the natural world and the manmade are complicated by the evidence of humanity’s creative and destructive impacts. Trash and recycled materials become the foundation for an exploration of nature in which junk is ‘a painterly medium,’ that destabilises narratives of human domination over the natural world.

Similarly working with narrative as though it is part of the material rather than something imposed upon it, Sibylla Robertson’s ceramics begin with the meaning imbued in the ceramic as it is built: in turn a sacred object or a functional form. The maker’s hand builds a world, not just an object. As with narrative-making for Ingold, no matter the form (the artist cites videogames alongside ceramics) for Robertson, the process of making is one of world-building.

It is worth noting that these practices are not merely conceptual. In fleshing out the idea with the material, the process of making is bodily. Laura de Carteret’s glass objects call our attention to this detail. The lifelike forms remind us of the act of glassblowing, the laborious process of producing; the reason that we refer to pieces of art as works.

Ingold makes it clear that it is not the basket’s form as a three dimensional object that characterises weaving as a craft. The surface made through the act of weaving is integral to its process. Acting on the surface, like drawing on paper, is a process in which the work of the hand is made as present as it is in sculpting. In Tango Conway’s drawings, this reality is made abundantly clear. Conway’s practice is not a matter of representational or non-representational drawing, it is ‘a celebration of drawing itself.’

As Ingold notes, there is no meaningful distinction between the weaver as a maker and the stone carver—the standard view of carving as an act of force upon the material narrows the narrative possibilities not only in the relationship of making, but also in the existence of the object. Hugh Crowley’s L’appel du Vide responds to the myth of Narcissus in the creation of a stone mirror carved using traditional techniques. Through the act of making, and the enaction of the object through performance, Crowley’s mirror demonstrates the two-way relationship between the object and the world around it. Literally and figuratively, it provides us with a point of reflection.

In the artists’ practices, making is an extension of the hand and of the body, neither of which can be cut off from the material once the object is realised. And on the other side of the artist, the material is of the world it comes from, and cannot be reduced to a medium for ideas: it is as productive of these ideas as the artist themself.

Exhibition Essay by Rebecca Hall

'nail polish footpaths' by lily golightly

Installation images by Docqment

Poster thanks to Kavil Patel using ‘Entangled’ by Tango Conway.

Chrystal Rimmer, Laura De Carteret, Sibylla Robertson, Tango Conway & Hugh Crowley

Notes on Reciprocity

August 21-September 29, 2024